"The Eight Aspects of the Precious Teacher" - Padmasambhava in Art and Ritual in the Himalayas

Catalogue essay (unabridged version) on the special exhibition at the Museum of Asian Art in Berlin, 28/11/2013

Unabridged catalogue essay

by Dipl.-Rest. (FH) U.S. Griesser

Thangkas (term thang ka tib: "something to roll") are structurally complicated three-dimensional objects traditionally made from a fabric (cotton, more rarely on canvas or silk), which is either embroidered or painted with opaque distemper, in the following referred to as the image part and consisting of an artfully elaborated fabric enclosure with a fine upper and a coarse lower fabric, wood struts as upper and lower end, two long ribbons and one or more silk coverings. (1) In a round cross section, the lower strut, which is often additionally decorated at the ends with ornamental buttons, allows for rolling up the thangkas towards the inner side of the image (Figure 1 and 2).

Fig. 1 and 2 illustrate thangka no. VIII (Inv. No. I 5980) from the Berlin Set (Dorje Drolö) before the treatment. The left image shows the closed thangka with museum cupboard as a working base: The silk cover conceals the image part completely. In the right picture the silken cover is draped in the traditional way. The required cord is missing at this thangka and was added provisionally for this picture. The bands usually remain at the front, but can also hang behind the scroll painting. Decorative buttons are missing in this thangka, so that only the ends of the wooden strut can be seen at the lower end.

In Tibet and Bhutan, thangka painting is one of the 13 techniques (2) of arts and crafts and it is taught in the Bhutan Arts and Crafts School in a 6-year study. (3) For thangka painting, it is common to use a thin, tightly woven cotton fabric, which is stretched onto a wooden frame and primed thinly with a mixture of chalk or gypsum based paste and the colouring of the image part is then polished thoroughly (4) in order to incorporate the primer intensively into the fabric and to achieve a surface as smooth as possible. (5)

(1) For the top fabric, silk damask or a brocade fabric is often used, a simple lining material made from wool or a kind of burlap or similar with mostly exposed image part serves as subfabric. The silken cover protects the image content from the eyes of uninitiated persons and as protection against flies and other contaminants. In Bhutan, the fabric enclosure is called Melong.

(2) http://www.apic.org.bt/bhutan-facts/arts-and-crafts/ states the following 13 techniques of crafts: „Paintings, carving, sculpture, calligraphy, carpentry, gold, forging silver and black, bamboo work, weaving and embroidery, pottery, masonry, paper and incense production.“ (Hit 12.09.2013).

(3) Institute for Zorig Chusum, Bhutan Arts and Crafts School, Thimphu, Bhutan in May 2013

(4) Oral testimony of a thangka painter, Bhutan traditional thangka shop near Jungzhi Paper Factory, Thimphu, Bhutan in May 2013

(5) Recently, factory-made, acrylic-containing primers and paints are increasingly used. Traditional materials such as primers made of glue and distempers are more expensive and are used today for special commissioned work. Oral statement by graduates of the Institute for Zorig Chusum, Bhutan Arts and Crafts School, Thimphu, Bhutan in May 2013.

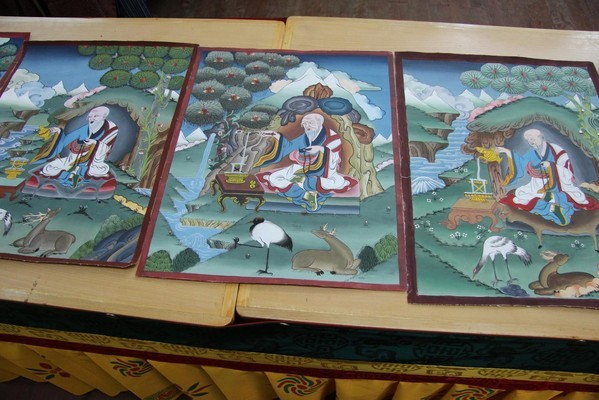

The sketch is mostly applied by stitch-tracing 1:1 in accordance to the respective painting tradition. Artistic freedom is only allowed in the decorative elements and in the design of landscape details (fig. 3 and 4). (6) Now, those paintings are increasingly offered unmounted and not traditionally mounted.

Fig. 3 and 4 With the same motif painted image parts of thangkas for sale

As a narrative and a religious picture work of the Himalayan area, thangkas are part of every altar, in religious ceremonies and serve the monasteries and the widely dispersed settled people as identification, information and meditation basis for obtaining higher levels of knowledge. Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, tutelary deities, symbols and mandalas are depicted on the thangkas, representing individual aspects of desirable qualities of mind which are developed by training mind and awareness. These include, for example, love, compassion, wisdom, generosity, healing, gumption, altruism, critical faculty, the resolution of selfishness and the co-responsibility for the world we live in.

The image part has a dense, expressively increased, symbolic language of form following strict specifications of great Tibetan meditation master and mystics, regarding formal and colour-related aspects. In the picture, the actual Buddhist doctrine is for example expressed as worshipping the depicted deity, as a tribute to a sick person or as an expression of the desire for physical or spiritual health. In this way, the sensual content of the presentation is transferred to a spiritual level. The painter must follow a specific order and only the one chosen by the master or the master himself may apply the skin tone and eyes of the characters at the end of the painting process, which corresponds to an ensoulment of the thangka. In contrast to the decorative frame in the Western tradition (with the exception of some framings of modern sculptures) the fabric enclosure must also be seen as an integral part of the artwork. (7) It is not for not for nothing that the often included piece of tissue in the lower part of the face fabric is called “door”. The top fabric is often assembled from individual, very precious and elaborately processed silk pieces (Fig. 03 and 04). Based on its expression and its traditional proportions, different traditions can be recognized. In addition to the stylistic differences, the specific structure and shape of the composition of the fabric can provide additional information regarding the origin, cultural significance and the chronological creation of a thangka. (8) The silk cover and the two hanging straps serve practical and decorative functions. (9) Only with the blessing of the finished thangka by a Lama, the thangka receives its sacred function.

(6) The author could convince herself of that in May 2013 in the Institute of Zorig Chusum owned business based on the very same subject of some of the final products of the studies of thangka painting that can be purchased there.

(7) Huntington, John C. in: Studies in Conservation, 15 (1970), The Iconography And Structure Of Mountings Of Tibetan Paintings, p. 190-205

(8) Jackson, David & Janice.: Tibetan Thangka Painting Methods & Materials, Published by Serindia Publications, 1984

(9) Griesser, Ute, thangkas – Scroll paintings of Tibetan Buddhism. Cultural significance and possibilities of preservation, in: VDR posts issue 10, 2002 p.201-203

Fig. 5 and 6 Detail shots of the original fabric enclosure of a thangka from the Berlin Set (Thangka no. VI, Inv.no. I 5976). To be seen is the right part of the bottom with a sewn-in logs and a red lining material that can only be recognized in a low angle view. The blue fabric is silk damask with a dragon motif (Chinese, Ming Dynasty 1368-1644). Based on its value, the silk was used very sparingly, not to waste something so precious on blind areas. If possible, even the smallest parts of silk are used according to the course of the pattern, seen in the right picture as a diagonal seam extending upward. In this assembly, a total of 10 to 11 pieces of fabric made of damask are used, which are mainly sewn in and rarely glued on.

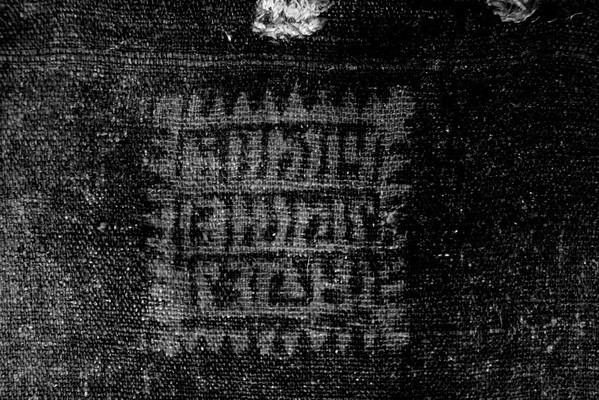

Fig. 7, 8 Detail shots of the back of thangka no. VI (Inv.no. I 5976):

On the left, an imprinted and brightly marked, hardly decipherable seal is to be seen under what probably is the original weaved ribbon, which is shown on the right with an indication of measurements. The weaved ribbon may have originally been fixed in the upper corners.

Fig. 9 and 10, On the left: daylight shot of seal impression of thangka no. VI (Inv.no. I 5976) in hanging direction.

On the right: Black and white shot of the seal, modified with an image editing program.

A thangka is connected in different ways with the acquisition of spiritual merit. The credit applies for both the painter and the client. As a gift for ritual purposes for a monastery, the merit is even classified as even more significant. Thangkas are extremely rarely signed, because the relationship between the principal and the commissioned work is foregrounded. The usage of finest pigments such as azurite, malachite, cinnabar, finely crushed pearls and gold dust for the image part is an equally meritorious deed as the making or the order of a thangka. The new painting can be classified as equivalent, or in terms of the act of painting as a spiritual practice and the related acquisition of a ritual merit, even as superior to the preservation of an original. (10) The practiced cultural asset in the country of origin experiences a different value in contrast to the artistic original of the west. The expression of this quality is reflected in the treatment of the exterior facade of the temple in a historic temple complex in Tibet (11): At the central wall, the original painting from the 18th or early 19th century is visible in an defect area of about 15 x 28 cm, which has probably been painted over in the 60s/70s with simple tools (Fig. 11 and 12).

Fig. 11 and 12 Close-up and magnified section of a revised original painting of an exterior wall of a temple in Kham/Sichuan. The light brown areas on the right are flaws of the original painting with visible clay covering.

The flaw allows a view of the same deity with outstretched left arm and forward reaching open hand with small changes in position and colour, but apparently in better quality in terms of painting technique. The revision is of simple style and involves risks to the original painting due to high material tension. (12) While the West might intend the preservation of the original first painting by removing the tense second painting, this revision seems to be justified in its extent to the Tibetans as it is part of the daily committed faith. We often encounter statements that ritual objects no longer meet their sacred function, not only in context with Buddhism, because of damage due to usage or age and are at best immured into a shrine or simply disappear and are replaced by new ones. (13; 14) Other reasons that may act in favour of re-creating artistic and cultural assets instead of preserving cultural and contemporary testimonies are financial reasons and procurement difficulties concerning materials for conservation and restoration. On the other hand, imported thangkas often receive Western glazing here. The usage of reactive materials for the framing and unfavourable climatic conditions can lead to accelerated decay of improperly presented objects. (15) „Other countries, other habits“.

Using the example of Bhutan, which also collects, documents, preserves and imparts their cultural artefacts with Western support (16), the author could convince herself in a practical course for Bhutan restorers working there that, beside the financial aid Bhutan and the adjacent Himalayan States need, imposing the allegedly better, since possibly scientifically more sound and longer acquainted with the preservation of art and cultural assets, Western concept of conservation and restoration, is not sufficient. Conservation materials have to serve as an example, which are developed by the West and brought into a context matching the respective circumstances and individual characteristics of the object for proper and efficient application, and are then transferred into an application product fitting the object. (18) In the absence of appropriate measuring instruments, these materials cannot be applied appropriately for the particular case or need, which can lead to fatal consequences for the object.

Due to differing opinions and circumstances, the question can be derived if there are adequate treatment and presentation concepts for cultural goods of other ethnic groups in the country of origin and the country of residence, without running the risk of losing sight of the cultural context and the significance. From the meetings and conversations, the visited cultural sites, as well as the experience of the practical course with several thangkas of hundreds years of age to edit, the author answers the question with "yes", if it comes to a collaboration of materials and methods following most up to date scientific approaches and needs and specially adjusted to particular, region distinct, local and climatic conditions. She calls this the “middle way”: The interaction of the views of the West and the countries of origin and the comprehensive understanding of the individual (Himalayan) cultures with their legacies can promote the development of common conservation models in both the country of origin and the country of residence: On the one hand, the Himalayan States, for example, obtain support and encouragement to intrinsically do research, document, preserve and convey. On the other hand, there is the opportunity for the Western nations of an increasingly globalized world, to include problem-solving approaches “outside the box” with intercultural competence, using the cultural assets of other ethnicities which are in their possession. (19)

The following image examples of Padmasambhava –thangkas, partially restored for the exhibition, give the reader exemplary insights as an expression of this interaction of both directives. (20) The use of a non-liquid medium for retouching provides a new solution to the "middle path".

Damage processes on thangkas at the example of the nine Padmasmabhava thangkas and their solutions

The variety of materials, the different aging and material behaviour and the cultural use of these sacred objects result in special problems concerning the conservation and restoration of thangkas: Thangkas consist of an interaction of flexible and rigid materials, from their constructive interaction and their handling can result damage. If not used, thangkas are often rolled for transportation starting from the bottom of the obverse, which inevitably leads to buckling of the pictorial structure, resulting in deformation of the base in form of waves or bulges through to kink folds, cracks in the paint and primer layers, loosening or loss of pictorial layers, thinning of colours up to complete loss of colour due to abrasion as well as tears in the image carriers and structural weakening of the fabric enclosure.

The atmospheric conditions and local conditions in the countries of origin favour contamination (e.g. oil stains and sooty adherences of the oil lamps and other residues of material) and the formation of damage due to light, climate and herbivore (UV exposure, temperature and moisture gradients, water damage from roof leaks or improper storage, microbial growth as well as damage by insects and rodents). Interventions such as substance losses due to detaching or separating the thangkas from the fabric enclosure to facilitate the transport or to dispose of improper colour, bulky or damaged areas and improperly performed repairs, preservation and/or restorations as well as improper framing and presentations to standards of Western aesthetics contribute to the damage.

The image parts of the nine Padmasambhava-thangkas mainly show changes in colour, water stains and spalling of colour as well as rubbed colours. The fabric enclosures are more recent except for two. In previous conservation and restoration steps including the consolidation measures of the complete image parts, the image parts have been detached from the fabric enclosure with two exceptions, to treat them separately and equip seven of the nine thangkas with new fabrics enclosures. Extremely small, more or less rectilinear piercings in regular intervals at the margin of the image indicate an altered seam and thus an earlier conservation/restoration. In preparation for this exhibition, the thangkas were left unchanged and treated in the horizontal or hanging state.

Colour changes

The darkening of painting stems not only from soot and dirt accumulations. (21) The latter could be reduced with a wet chemical method which is harmless to the image structure. The Western conservation and restoration science wants the contamination removed, as it causes more adherence of dirt to the particular object, while the components of the debris and root can trigger or contribute to negative deterioration progresses in the material structure. At the same time, atmospherically induced colour changes, which are to date often described as “patina” and include (deep) pollution, represent an important characteristic of authenticity, which takes age and function into account. "The Middle Way" provides, without any damage, an improved readability in a suitable presentation, but preferably avoids total cleansing that targets the original colouration and often endangers the object. (22)

The rather opaque, almost white appearing residues (23), as to be seen in the details of thangka Inv.no. I 5977, lead to a cover of the highly nuanced decoration of the garment generated with the brush and gold powder, which stands out even more striking through the general darkening of the colour (Fig. 18 on the following page, fig. 13, 14, and for comparison without eye-catchers Fig. 15). The image viewing is negatively influenced through this optically distorted reproduction of this rich colour. The Western conservation and restoration science intends the reduction of these "eye-catchers" into the original state, which experientially also happens in the countries of origin due to the strict traditional colouration in paintings (24).

(10) Bruce-Gardner, Robert in Steven Kossak, Jane Casey Singer, 1998: Secret visions. Early paintings from Central Tibet, exhibition at the Museum Rietberg Zurich and The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 06.10.1998 to 16.05.1999, p.193-206

(11) Monastery of the Gelug School near Kandze, formerly province of Kham, today China's Sichuan Province

(12) The observation is based on personal experience, made by the author at a practical work operation in eastern Tibet in 2002. The project of the Tibet Heritage Fund charity space (THF) which operates in the Himalayas, among other things, fragile wall paintings inside the main temple of a temple complex were preserved and restored.

(13) Seen in Dumtse Lhakang, Paro, Bhutan on 10/05/2013: Prayer mills of the Kora have been replaced not too long ago. The old prayer wheels are completely unprotected but still piled up in a wall niche in a decent state of preservation.

(14) Swiss Guest House, Bumthang Valley, Bhutan on 04.05.2013: Interview with the Swiss innkeeper and cheese producer Mr. Maurer, who has been living in Bhutan for 47 years. According to him, thangkas of the mid-80s were removed from the nearby monastery. The people looked forward to the new paintings. The old thangkas were never seen again, possibly burnt as conventional.

(15) Lack of knowledge, improper use of traditional custom and thoughtlessness can also shorten the lifetime of artistic and cultural heritage.

(16) "Even severely damaged thangkas are to be and kept preserved, because they represent the history of the monastery, the Buddha's teachings and thus have become the carrier of identification for their monastery/line, which cannot be achieved by a newly painted thangka." This is analogously the result of conversations of two monks in Throngsa Dzong who are responsible for the thangkas, with the monk responsible for the thangkas of the privately organized Nyimapa monastery Gantey and a restorer at the National Museum in Paro. The interviews were conducted by the author with the assistance of a Bhutanese tour guide in preparation for the two-week course in May 2013 in central and western Bhutan.

(17) Following the invitation of the Director of the Department of Culture and Cultural Property Chief Officer DCP, the author conducted a course for six local official and museum conservators from 13.-26.05.2013 in the Department of Culture in Thimphu. The objective was the exchange and intercultural conceptualisation of several thangkas that had to be treated for conservation and restoration. A donation program with continuation of these courses is planned. In Bhutan as in Tibet, the Vajrayana Buddhism is the state religion. As a developing country, it is also dependent on donations.

(18) Conservation and restoration materials are mostly made individually out of pure substances whose chemical composition is known. Customary materials, if available, often display unfavourable aging characteristics contingent on their additives and therefore involve unforeseeable potential dangers for the materials that come into contact with these artistic and cultural assets.

(19) The author encourages to achieve a transnational and interdisciplinary exchange through a digital network for thangkas and other sacred objects. Introduced at the forum on the Conservation of Thangkas, ICOM-CC 15th Triennial Conference, New Delhi, India, September 26, 2008: “Presenting, Handling and Treating Sacred Thangkas According to Western Standards and Respecting their Cultural Context – An Achievable Common Purpose?”

(20) The conservation and restoration actions on the nine Padmasambhava thangkas are constrained solely to the painted surfaces, not to the textile areas, and the montage for the exhibition presentation.

(21) The colour darkening of all nine thangkas is mainly caused by previous strengthening actions. The yellowing tendency of the aged fixative, presumably based on polyurethane resin, results in a browning of the colour surface as a function of the layer thickness and the degree of oxidation of the resin. These colour changes should be excluded from the current conservation and restoration. It would be desirable to securely identify the strengthening material to possibly develop methods for its removal.

(22) In the total cleansing, the image part is separated from the fabric enclosure, the painting is placed on an absorbent pad facing upwards and is being pruned of root and debris through wet chemical processes, partly in combination with negative pressure, beginning at the top going downwards, possibly exchanging the absorbent pads. To the author’s knowledge, this method is practiced occasionally in the West and in the Himalayan region. Due to the barely controllable effects of swelling and shrinking processes in the image structure and, in comparison to age and cultural use, inconsistent cleansing result, the graduates of the practical course in the Department of Culture, Thimphu, Bhutan, are not entirely positively open-minded regarding this method during the tests and surveys which were carried out in May 2013. Rather, the graduates adopted a wait and see attitude towards the cleansing results in a heavily polluted image part of a centuries-old thangka, which had been purified during the course of the training following to the principles of the middle path. After the colour completion of the defects and the optical harmonisation of dark edges, all graduates were amazed at the visual result. They were positive about the use of the middle path.

(23) At low magnification, an amorphous-looking, small-scale, relatively loosely adhering to the paint surface material can be seen under the stereo microscope.

(24) Insofar as sufficient funds are available. Oral statement by graduates of the practice course at the Department of Culture, Thimphu, Bhutan in May 2013

Fig. 13 - 15

The images on the left and in the middle (enlarged section) show whitish material residues that occurred on certain colour ranges of the nine thangkas and could be removed physico-chemically. The image on the right shows the section after the treatment with the now again visible decor of the undergarment of Padma Gyelpo, a royal appearance of Guru Rinpoche (Thangka no. IV, Inv.no. I 5978).

Supplementation of a depicted minor character’s eye

Another example of the interaction of Western standards of conservation and restoration science and those of the country of origin is detectible inspecting the same thangka of the series of nine (Inv.no. I 5978), namely the addition of an eye to the small middle figure at the bottom of the painting. According to the Western standards, the area of just 5 x 3 cm, which is far below the observer’s central view, could be left untreated in the retouching. The right eye (as seen by the observer), still visible to some extent, could be left as it is to preserve the historical character, also for the permanent capture of the loss of an eye. In Vajrana Buddhism, only the eyes lead to an ensoulment of the character(s) shown. A rudimentary visible eye would take away the figure’s soul and thus hinder the contemplation of the meditator. The compromise of both standards intends the completion, but, in a close-up, reveals the subsequent supplement of the section here shown enlarged according to scale, to take the Western guideline of discriminability between the original and later addit

(Fig. 16 and 17).

Fig. 16 and 17

Detailed view of a secondary character below the central figure, in the left image before and in the right image after retouching. In reality, the picture section measures about 5 x 3 cm.

(Thangka no. IV, Inv.no. I 5978)

Treatment of water stains, loss of colour, colour rubbings and "patina" without separating the image part from the fabric enclosure

Fig. 18 and 19 Upper part of thangka no. IV (Inv.no. I 5978), on the left before and on the right after the conservation and partial restoration.

The image part of thangka no. IV (Inv.no. I 5978) showed significant loss of colour and water stains (Fig. 18). The dirty, extremely moisture sensitive painting is dissolved in direct contact with aqueous liquids and completely washed out in prolonged exposure. If initially the binder is dissolved and the colour and primer ingredients soften up due to continuous moisture penetration, the adhering contaminants also start moving: The liquefied material is transported onwards due to the absorbency of the still dry pictorial structure and is accumulated elsewhere (Fig. 20). This results in dark margins, which, based on experience, can neither be removed fully nor without any damage to the respective or surrounding areas. An optical harmonizing by retouching is possible without effacing the damage completely. The water stains can still be seen. Thus, the Western guideline is met. The standard in Bhutan intends the use of same colour materials to fill the defect and dark discoloration by controlled application of distempers according to the colour of the surrounding original painting. The glue is usually obtained from bones, skin and tendon components of cattle and yaks (25) and mixed with colorants of mineral and herbal origin or from artificial production and diluted with water, and then applied in a liquid state and at least lukewarm (26) with a fine hair brush. (27) After retouching, the defects are no longer visible as such and thus cannot be distinguished with the unaided eye and without scientific aids. The light stability of the colorants used is not always guaranteed. Commercially available water-based inks are also used, such as those used for schools (28). The conception of the country of origin has therefore no aspiration of removability of these subsequent restoration treatments. The original painting could be damaged in the attempt to remove the retouching medium due to the essential use of aqueous systems. (29) The Western conservation and restoration science is hoping to use light-stable systems for retouching and strives for possibilities to remove such treatments. Adding liquid binders to the medium for retouching is ineligible in the opinion of the author, as the treatments cannot be fully reversed in reality. (30) The "middle way" logically represents a retouching medium without addition of liquid binders and solvents - this approach was also applied in the retouching treatments for the nine presented thangkas. (31) The retouching medium was applied exactly where it was needed. (32) The material is only superficial, and thus can easily be removed. With minimal amounts of this retouching material, dark water stains can be brightened and finest colour nuances of abraded areas and flaking can be adjusted. (Fig. 19 and to directly compare Fig. 20 and 21). The example of the nine Padmassambhava thangkas highest controllability for retouching, improved readability and the claim of a differentiation between original and belated supplement has been achieved without destroying the authenticity of the centuries-old thangkas. Authenticity means maintaining the functions of identification, information and object of meditation, whilst also making and keeping the thangkas experiencable as contemporary documents. And thus to draw attention to the carriers of meaning of the Himalayan cultures, former used in everyday life.

Fig. 20 and 21 Thangka no. I (Inv.no. I 5977), detail from the left side with 5 x 3-cm section of a water stain, on the left before and on the right after retouching. The water stain is still recognizable to a small extent.

(25) According to the graduates of the practical course at the Department of Culture, the glue in Bhutan was for decades obtained from bovine components and not, like in Tibet, from the yak.

(26) The adhesive glue solution would gelatinise while being cooled and the colour would no longer be paintable (note of the author).

(27) According to the present graduates of the practice course in the Department of Culture, given that sufficient financial resources are provided.

(28) Camel watercolour tubes, produced by member of the Arts and Creative Materials Institute, Boston, USA: According to the graduates of the practical course in the Department of Culture used as a low-priced retouching medium.

(29) In the western conservation and restoration ethics, however, exactly this possibility to undo restoration treatments without any damage, is demanded. At the same time, the use of authentic materials is recommended, especially if they are of particular significance as in thangka paintings. However, this leads to the aforementioned dilemma of not being able to remove the restoration treatments without any damage. In addition, authentic colours and binders are often no longer available in the desired state to match the original. If creating the colour composition exactly matching the original would be possible, internal and external chemical and physical processes and contaminants would inevitably lead to a change in colour in the layer over time. The colour medium matching the colour in its original appearance would have to be artificially patinised by adding other colouring ingredients to serve as a retouching medium to achieve the aged appearance of the thangka painting. This runs contrary to the aspiration for authenticity, because the original colour composition has to be changed. So far, the other Western restoration approach remains. This approach relies on synthetically produced, artificially mineralized and synthetic colorants which are rubbed in stable, artificial resin and offered as a high-quality light-stable retouching colours. Even after many years, these should be removable with weak organic solvents that are not dilutable with water and thus hardly affecting the distemper paintings.

(30) Aqueous systems, as well as colour mediums, which could be used with a synthetic, non-aging binder containing weak organic solvents that normally are harmless to the object, uncontrollably penetrate the structure due to the high substrate absorptivity and would not be removable without damage. It has yet to be scientifically conclusively investigated to what extent the adhesion of the colour components of the retouching medium on to the textile fibre structure and the more or less absorbent and porous material structure of primer and paint can be reduced or eliminated by pre-treatments such as stabilisation, puttying and isolation of the areas that are retouched. Furthermore, the considerably higher expenditure of time and the risk of covering original areas and possible material tensions have to be taken into account.

(31) An exception is the described supplement of an eye of a minor character.

(32) It was attached by pressure. The image structure must be able to withstand the spotted pressure. Changes in the degree of gloss are possible.